Business Idea Testing for New Entrepreneurs: How Experimentation Saved Thousands of $$$

And so it begins…

Some months ago, I sat down with a new client who initially had a business idea to design and build a B2B research app. Curious, I asked ‘why’ and the subsequent conversation was one I’ll never forget.

PS: I asked my client if I could share this and was given an express right to with some anonymity. So I will refer to my client as ‘Client X’ with no mention of a specific gender.

Client X explained the ‘why’, and I followed up with two questions: ‘Why should people use this app?’ and ‘How do you know people will use it?’. There was an awkward silence before responding, ‘Well, that’s why I’m building the app’ 😂.

In my typical animated style, I excitedly began discussing concepts like ‘experiments’, ‘business models, ‘viability’ and other terms. However, after a moment, I paused to check if Client X understood what I said. Another awkward pause ensued, followed by a smile, and I realized that my words had been lost on them. We both burst into laughter.

I had mistakenly assumed that everyone understood the concept of experimentation and that Client X comprehended all the terms I was using. I had to start over, this time explaining everything with annotations.

This is what I aim to do with this article. I’ll share the step-by-step process I used to design, execute, and manage an experimentation project with my client.

The goal

To provide more context, Client X is a one-person team aiming to build an application to solve a problem for businesses. Our approach to experimentation was based on the size of the team and the resources available, but I’ll note what I might do differently with a larger team.

Disclaimer: If you’re experienced with experimentation, this might not be for you. However, you could still skim through if you have some spare time and are curious about my unique perspective.😁

Business Idea Testing

Testing your business ideas isn’t a new concept, yet it’s often overlooked. From my experience, many people, especially those new to entrepreneurship or innovation, lack the necessary know-how.

The interesting thing is testing ideas can be applied to both new business ideas as well as at a product level. This article will focus on testing a new business idea.

A lot of concepts I’ll discuss arise from books, courses, and my personal experiences with my client. I’ll also provide links to additional resources to guide you on your journey.

What is business idea testing & why should you care?

In the words of Richard Feynman….

My question to you is ‘Why would you want to invest a significant amount of money into a business idea, only to realize later that you shouldn’t have in the first place?’

The journey from conceiving an idea to turning it into a business is fraught with risks and uncertainty. Testing your idea is one of the best ways to reduce these risks and save time, energy, and resources. Something to note is that experimentation doesn’t necessarily eliminate all risks but significantly reduces them.

It’s worth noting that idea testing isn’t only for companies with tech products. Even traditional brick-and-mortar businesses can use testing to minimize the risks associated with their ideas.

I discussed more on why small businesses should foster a culture of experimentation in my article Startups are Experiment Machines.

Let’s dive into the details…

Figuring out your business model, a prerequisite for testing an idea

First, you need to have your business model figured out. To start testing a business idea, you should have:

Narrowed down to an idea that’s solving a problem.

A business model. According to Wikipedia, your business model describes how your business creates, delivers, and captures value, in economic, social, cultural, or other contexts. (I love this simple definition).

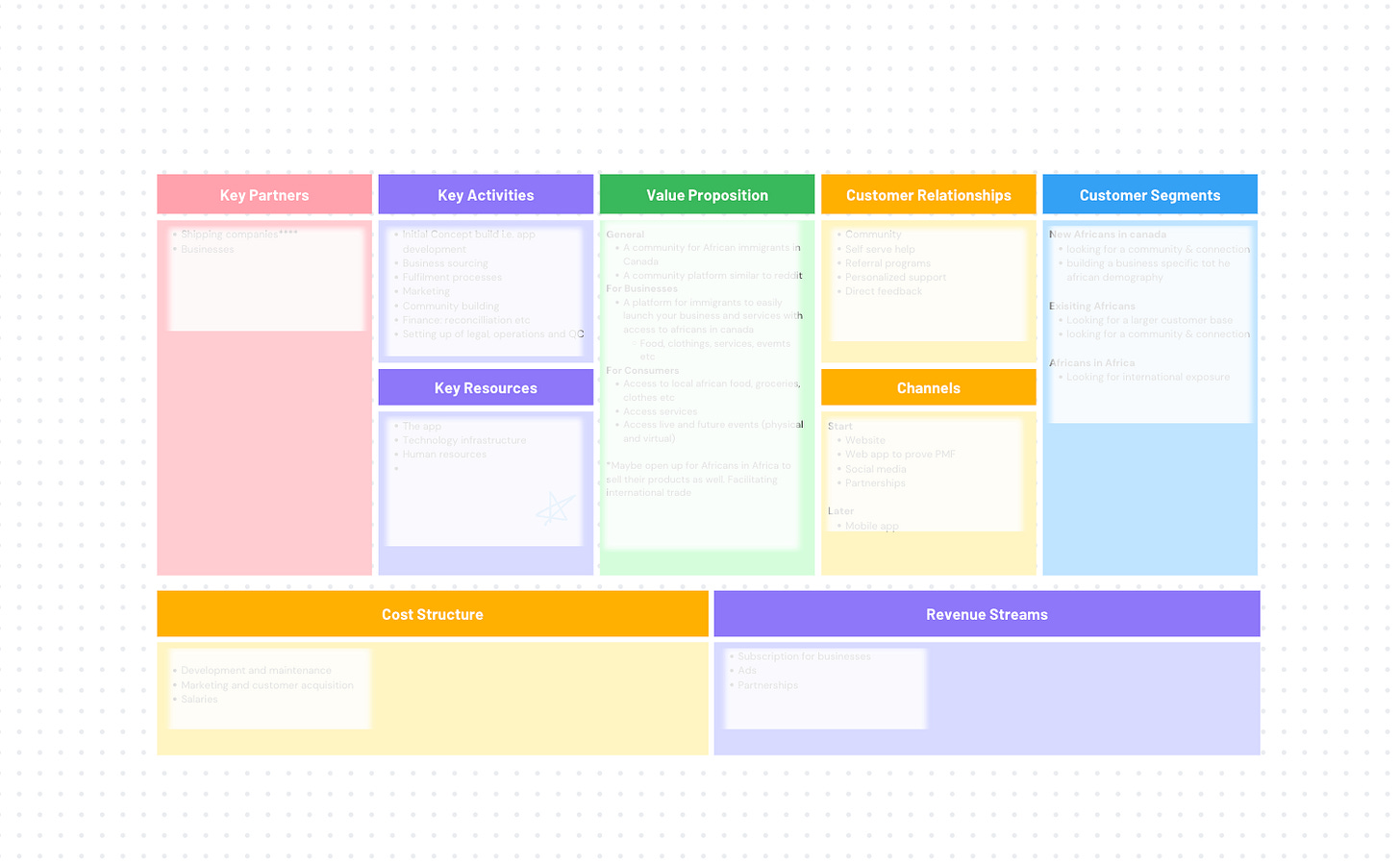

One tool I use to map this out is the Business Model Canvas. Its simplicity makes it easy for novices to engage and own the process.

To learn more about business models and the tools you can use to map out your model, I recommend the book Business Model Generation by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur.

Back to Client X

Client X had worked out the business model before our engagement, so I did some coaching on how to visually map it out using the popular Business Model Canvas and Value Canvas.

I might write about this in future articles. Maybe.

Now that you have your business model, it’s time to test…

In summary, testing involved:

Identifying our hypothesis

Designing and executing our experiments

Analyzing & synthesizing learnings

Taking actions

Hypothesis

Think of a hypothesis as an educated guess. And because it’s a guess it can either be true or false.

A hypothesis or hypothesis statement seeks to explain why something has happened, or what might happen, under certain condition.

- Tim Stobierski for Harvard Business SchoolHypothesis is a statement that must be true for your business to succeed.

- Tendayi Viki for Strategyzer

*Ps: There are 2 types of hypothesis: Alternative and Null. We’re discussing the alternative hypothesis here. Don’t worry about these 2 terms for now.

What you’ll be testing are your hypotheses and assumptions before implementing them. It’s therefore important to identify and write out these hypotheses.

An easy way to do this is to revisit your business model canvas and go through each block, asking yourself the question, ‘What must be true in this block for this idea to work?’

‘What must be true in this block for this idea to work?’

Back to Client X

First, we conducted an exercise where we went through the BMC we had initially mapped asking ourselves the same questions. We generated a lot of hypotheses. 😂

Given the limited resources, time, and manpower, we focused on the hypotheses generated from the ‘customers’ and ‘value proposition’ blocks. We selected these two because:

Validating them is crucial, as an idea without a market is likely to fail.

We could only manage multiple experiments around these two; anything more would be overwhelming.

The process above here is referred to as assumption mapping which is a subject area on its own but won’t dig into so as not to overwhelm you. Assumpting mapping helps you define and prioritise your hypothesis. The process of prioritising involves evaluating each hypothesis against the level of importance and if you have proof of evidence to validate or invalidate it. You can learn more from this webinar by David Bland.

We spent a considerable amount of time framing the hypotheses to ensure we:

Can verify whether they are true or false. A vague hypothesis is difficult to validate or invalidate.

Have a clear outcome.

Are testing for one variable per hypothesis so that we can easily identify possible cause-and-effect relationships.

This was critically important, as a weak hypothesis would lead to a flawed process and result.

Experiments

Now that we have our list of hypotheses, let’s design our experiments. In simple terms, an experiment is how we plan to validate and invalidate our hypothesis.

For each hypothesis, we:

1. Selected the experiment methods to use

Note that I used the plural — methods — as it’s always recommended to run multiple experiments per hypothesis. This approach strengthens your learning and gives you more confidence to make the appropriate decision.

I know when a lot of people hear experiments all they hear is A/B testing but there are so many tools to use within our arsenal to test.

You can learn more tools from one of my favorite books ‘Testing Business Idea’ by David J. Bland and Alex Osterwalder.

Back to Client X

We had a total of 5 hypotheses with 20 experiments, with a minimum of 3 per hypothesis. This may sound like a lot 😂, but it wasn’t. I coached Client X to use a mix of simple & medium to execute methods.

Another thing to consider is using a mix of methods that range from discovery to validation, attitudinal to behavioral.

One thing to be cognisant of when selecting your method is the ‘say-do gap’. The say-do gap is the difference between what we say and what we do. We all do this and it is simply part of being human: being affected by things we do not realise and sometimes acting differently than intended because of it. E.g. On my way to work I might promise my colleague to bring him a cup of coffee but might miss my train and have to take a different route to work hereby preventing me from getting it. This happens a lot in research and experiments where users say they will do A but in reality do B when the event happens. To combat for this I recommend you include methods that will gives you the opportunity to observe their behaviours.

For one of the hypothesis we opted for the following experiment group:

Discovery survey to get a broad opinion on the extent to which this problem matters

Desk research into discussion forums to understand what people are saying

Storyboarding + One-on-one Interviews to share a rough description of our ideas and gather direct feedback.

Simple landing page made with a free tool with a clear ‘join the waitlist’ CTA to gather behavioral data on potential interest.

Simple ads & Email campaigns to support the ‘simple landing page’ experiment.

2. Sequenced the experiments

It’s highly recommended to document the sequence of your experiments. This will help you identify at a glance which experiments can be run at the same time and which ones are dependent on others.

Back to Client X

For each hypothesis, the experiments were grouped and sequenced so we could start from the easiest and cheapest and work our way up to the ones requiring more effort and resources.

You can find a similar experiment setup guide here.

3. Identified the metrics we wanted to capture for each experiment and defined what success looked like

Tracking is crucial. How can you make decisions if you aren’t tracking? For each hypothesis, we had our metrics and targets for what success would look like.

Back to Client X

One of our metrics for a hypothesis was the ‘Number of people to join the waitlist’, and success was defined as a minimum of 150 people joining the waitlist. If we reach this target, our hypothesis will be validated.

PS: Getting a target value required a benchmarking process I won’t discuss here.

Once this was mapped out, we moved into execution.

Learnings, Insights & Application

Back to Client X

We used a dashboard in Notion to help us track and document our findings. We held weekly catch-up sessions dedicated to reviewing the data and understanding what it was telling us. More regular sessions were held to review, document findings, and make necessary tweaks to the experiment if necessary. This also made synthesis and analysis easier.

As we synthesized findings from each experiment, if the findings validated our hypothesis, we moved on to the next experiments in the sequence. Conversely, if an experiment invalidated our hypothesis, we skipped the rest and declared the hypothesis invalidated.

For example, when we ran the discovery survey, participants seemed excited about the idea. Then we moved to customer interviews, and although interest dwindled, we still received some positive reactions. However, these reactions were a far cry from the ones we got when we had a landing page with mockup visuals of the product asking people to join the waitlist.

After 1.5 months of running experiments, our different learnings cumulated into a wealth of insights.

Action

We learned a lot, which gave us a clear picture that the idea, as it was, wasn’t going to achieve the acceptance that Client X had envisioned. So, it was time to take action.

Client X had the choice to:

Maintain the market but tweak the value proposition by leveraging modern technology like AI.

Pivot into a completely new product area for the same market.

Pivot into a completely different market solving a different kind of problem.

I will leave out the decision Client X went with.

Managing Experiments

Routines

As a small team, we had multiple weekly check-in routines to stay on top of our experiments, track findings, analyze insights, and adapt learnings to make decisions and take action.

We used a Kanban board on Notion to visualize and get an overview of all activities. For larger teams, more routine activities like stakeholder reviews and retrospectives may be necessary. As much as possible, try to maintain some agility around your routines.

External Coaching

If you’re new to testing ideas, one way to optimize your experiments is by leveraging a coach. A coach will guide you on the journey, making it easier and less daunting. I coached Client X all the way and was actively involved in the execution.

You can learn more about how we support founders and businesses to experiment with their ideas here.

Key Points to Note

Use low-fidelity: For experiments that required some sort of prototype, we created scrappy prototypes using tools like Notion, Airtable, free Webflow templates, and so on. This helped reduce costs and increase speed.

Leverage cheap experiments: Client X had limited resources, so we started with experiments that cost $0 and gradually moved on to experiments that involved money. However, we set a cap per hypothesis. After all, the goal is to avoid spending too much money in the first place.

Run concurrent experiments: Although a few experiments were sequential, i.e., the output of a previous experiment was an input for the next, most experiments ran concurrently. Proper documentation and tracking ensured we weren’t overwhelmed.

Use a control: We limited the changing variables to one per experiment. Tweaking many variables means there are many more moving parts, making it more difficult to discern cause and effect, i.e., which change in variable contributed to an observed effect.

Final Note

Was it a smart business decision to forego a design project that would have guaranteed more revenue in favor of a coaching gig? Maybe not…Lol. But the entire process has positively impacted my client. I do not doubt that when Client X is ready, I’ll be their go-to for future projects.

Did you find this insightful? Do you have opinions to share? Or perhaps some general feedback? Please let me know in the comments. Thank you for reading!

Do you want to learn more about how I test business ideas for my clients? Join my upcoming webinar where I’ll walk participants through creating a strong hypothesis and designing and organising experiments to achieve the desired outcome.

Additional resources

You can find my experiment setup template here

Testing business ideas by Alexander Osterwalder and Yves Pigneur

Business model generation by David Bland and Alexander Osterwalder

Experimentation works by Stefan Thomke

Lots of articles online 😁